Introduction

This is an introduction to the biomedical research enabled by nuclear physics and the technologies employed at the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (JLab), looking at how the specific examples of radiation therapy (stereotactic radiosurgery – SRS) and medical imaging are similar or different to JLab accelerator operations and experimental work. Cancer therapy with SRS relies on nuclear physics radiation simulation tools and high performance computing (HPC) to simulate complicated radiation therapy machines, guide dose delivery, and study the relative biological effectiveness (RBE) for treatment of high energy particles as they traverse biological material.

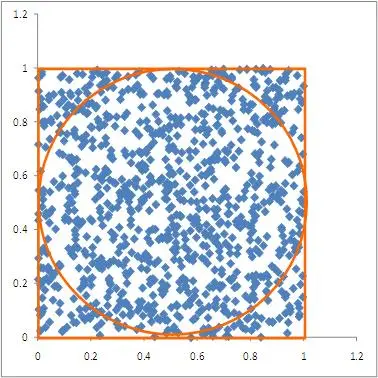

Monte Carlo simulation (meaning to roll the dice, adapted from the Monte Carlo casino in Monaco) has many advantages over explicit analytical calculations (either done on paper or with tools like Mathematica), including the ability to preferentially explore regions of a parameter space that are of particular interest with increased statistical precision, and the ability to describe arbitrarily complicated systems, as long as the processes and interactions taking place are sufficiently factored away from each other. The conceptual approach of Monte Carlo is very useful across science and engineering, with applications ranging from medical treatment planning to aerospace prototyping, protein folding and chemistry analyses, environmental risk analysis, and diffusion or sampling machine learning AI. Nuclear physicists at Jefferson Lab primarily utilize Geant4, the standard Nuclear Physics radiation simulation packages at the heart of Jefferson Lab’s various experimental programs and at the heart of some medical treatment planning system (TPS) and accelerator design software packages.

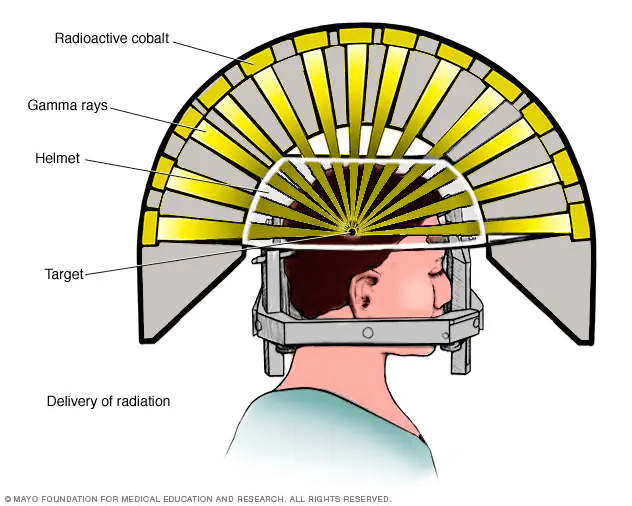

A traditional modality of radiosurgery to consider is that coming from static radioactive sources, such as the Gamma Knife system that utilizes radioactive Cobalt-60 irradiating gamma rays (high energy photons resulting from nuclear radioactive decays) from multiple angles onto tumors.

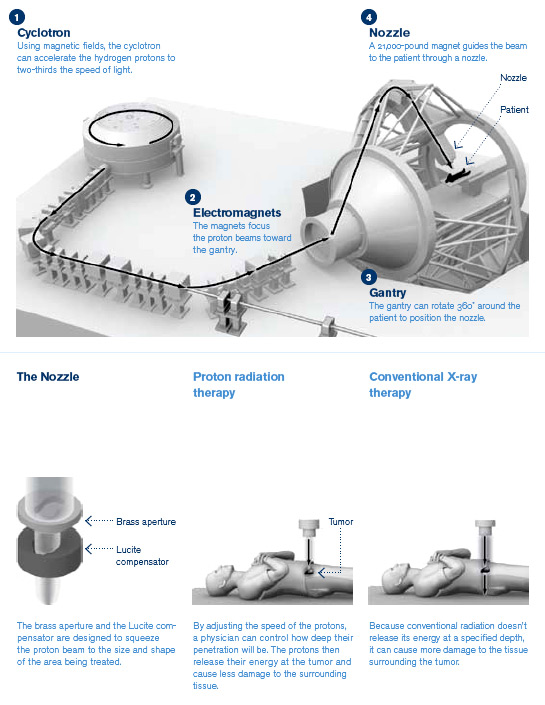

This is not to be confused with total body irradiation (TBI) radiation therapy, which is intended to irradiate the whole body with X-rays, for immunosuppressive or other purposes. Gamma Knife radiosurgery and others like it will be referred to as Stereotactic Radio-Surgery (SRS) going forward, though is sometimes referred to as Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT). An alternative, more modern, expensive, and versatile engineered modality to compare to SRS is the use of proton beams from accelerators for more targeted radiosurgery, called Proton Therapy (PT).

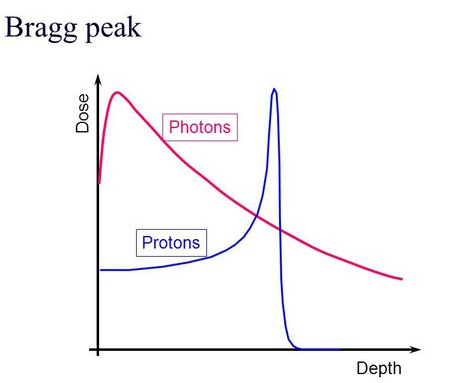

Proton Therapy is a recent development enabled by cheaper and smaller particle accelerators, similar to the CEBAF accelerator at JLab, which takes advantage of the increased localization of the energy deposited by the protons, which are heavier charged particles, compared to massless and chargeless gamma ray or X-ray photons. The figure shows the treatment planning system (TPS) dose-profiles of a brain tumor irradiation using proton therapy (left) and with photons (right).

As you can see, the excess dose outside of the central region is reduced by the PT approach, which also requires fewer angles of irradiation (3 vs. 7 in this example). This is explained by the “Bragg Peak” effect whereby the energy lost by a massive particle increases as the momentum of the particle decreases.

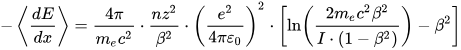

The loss of energy increases as the particle’s momentum slows down, following the Bethe-Bloch formula for energy loss while passing through matter. More can be read on this topic in the Particle Data Group (PDF) chapter on the passage of radiation through matter here: https://pdg.lbl.gov/2019/reviews/rpp2018-rev-passage-particles-matter.pdf

The equation above is the Bethe-Bloch formula, where you can see that the energy lost while traveling some distance through matter (loss of energy over distance -dE/dx) is inversely proportional to momentum (1/m*beta^2). It is also proportional to z^2, where z is the atomic number (number of protons per atom) of the medium through which the particle is travelling. The z dependence means knowledge of the material composition for treatments is key and that a range of material densities and distributions may be distinguished by passing radiation through that matter and seeing what makes it to the other side. The details of the formula beyond these proportionalities are not immediately important for this discussion, but they do play a role in many nuclear physics experiments and radiation detection techniques. This formula is not useful for massless radiation, as you can see from the mass present in the denominator causing a singularity. Massless radiation (photons) interacts primarily through the photo-electric effect, whereby the photon excites an electron out of inner orbital energy levels of atoms it encounters, but also scatters away from its original trajectory through other mechanisms, such as Compton and Rayleigh scattering.

For massless particles (photons) their radiation vs. distance travelled is exponentially reduced vs. depth, when approximated as a linear attenuation of energy absorption passing through matter, though there is some scattering that complicates the picture and makes the dose profile fuzzier around the edges. For photons, much of the energy is deposited at the entry range, which is compensated by irradiating from many angles to increase the dose in the central target region. For proton therapy, in addition to having less radiation lost in the entry regions and fewer angles irradiated, also the central region dose is more tightly controlled. This permits irradiation of tumors in sensitive small areas, such as the brain or prostate, and provides the improved precision necessary for treating smaller patients such as children.

In addition to comparing SRS vs. PT, we can also consider the use of tracking and energy sensitive radiation detectors to PT sites such as the Hampton University Proton Cancer Institute (HUPCI, or also called HUPTI, replacing “Cancer” with “Therapy”). There such detectors can support medical imaging research, taking protons shot with sufficiently high energy to pass through the patient and come out the other side to probe the biodistribution of tissue densities. The amount of energy lost by the proton as it traverses the patient will be proportional to the amount of material it interacted with, through the Bethe-Bloch formula, allowing for 3D reconstruction of the interior through Computed Tomography (CT), just like in the X-Ray CT, but with the same apparatus and species of radiation as is used in Proton Therapy treatments.

This discussion should have provided an overview of the physics principles at play in cancer treatment and diagnostic imaging enabled by the nuclear physics knowledge. The subsequent sections will cover the lifecycle of nuclear physics research at the lab to provide additional context for how and why physics lies at the heart of medical diagnosis and therapy.

Overview of Jefferson Lab: Connecting Nuclear Accelerator Experiments to Nuclear Medicine

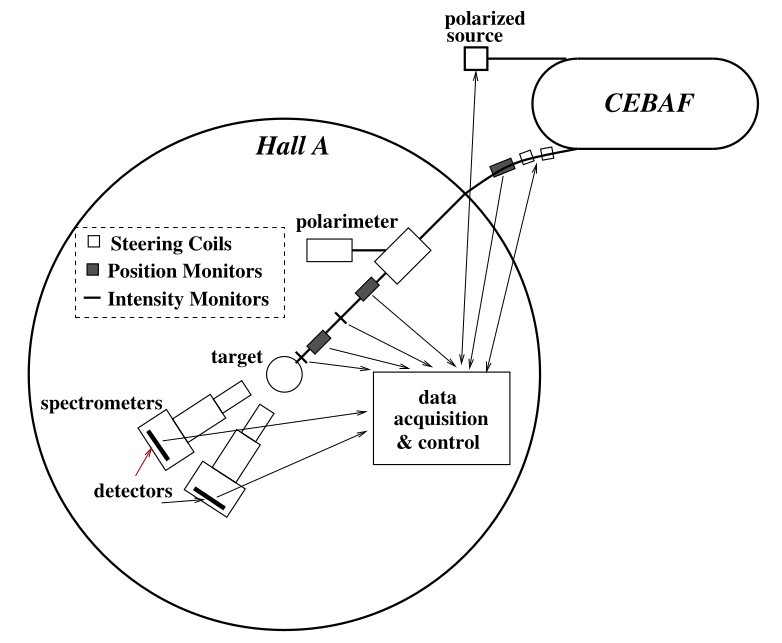

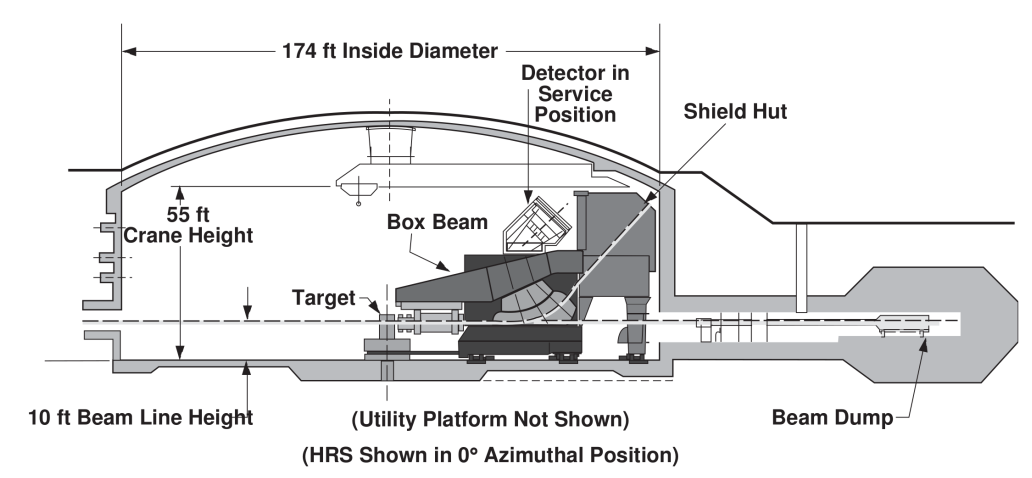

The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (TJNAF, or Jefferson Lab, or JLab) is part of the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science’s nuclear physics user facility system. A user facility is a place where academic researchers can propose experiments, get approved to run, and receive accelerator beam time. Jefferson Lab has 4 experimental halls (A, B, C and D), as well as several basic research and development (R&D) groups, operations groups, and support groups. The Radiation Detector and Imaging Group is an R&D group focusing on developing detector technologies and imaging systems using the nuclear physics techniques common in the 4 experimental halls.

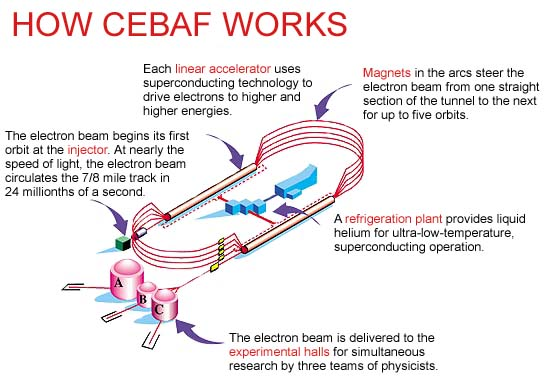

Jefferson Lab is centered around the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF) which is an electron particle accelerator that operates with high beam current and a high degree of electron polarization. The electron beam is produced by a laser system in the injector and then circles around the accelerator several times, adding 1 GeV of energy (more than 2000 times the at rest, mass only energy of an electron) through each linear accelerator segment pass. After 6 passes of the entire accelerator, recirculating through magnetic bending arcs on the west and east sides of the system, the beam will have reached 11 or 12 GeV and is ready to be delivered to the experimental halls for scattering against fixed targets.

The Biomedical Research and Innovation Center (BRIC) was recently founded at JLab to serve as a front door for the lab. Its goal is to facilitate conversations inside and outside of the lab environment regarding potential biomedical applications of technologies and ongoing research at the lab. Many of the pre-clinical imaging systems developed in the Radiation Detector and Imaging Group naturally fall into this category, as well as machine learning applications with the Data Science Group and compact accelerator applications for biological irradiation and sterilization systems from the Superconducting Radiofrequency Institute (SRF Institute) and the Center for Advanced Studies of Accelerators (CASA), among others.

Life-cycle of a Typical Nuclear Physics Experiment

A typical nuclear physics experiment follows the following life-cycle:

Theory

Before any experiment is propose there must be a scientific question to be answered. This is where theory comes into play. Theoretical physicists develop models of the fundamental physics of the universe, but those models are often difficult to use to predict the complex interactions and many-body conditions that the physics we encounter at the sub-atomic nuclear scale. Theorists then develop computational tools and effective theories that reduce the complexity and attempt to describe simpler interacting systems that approximate the full model.

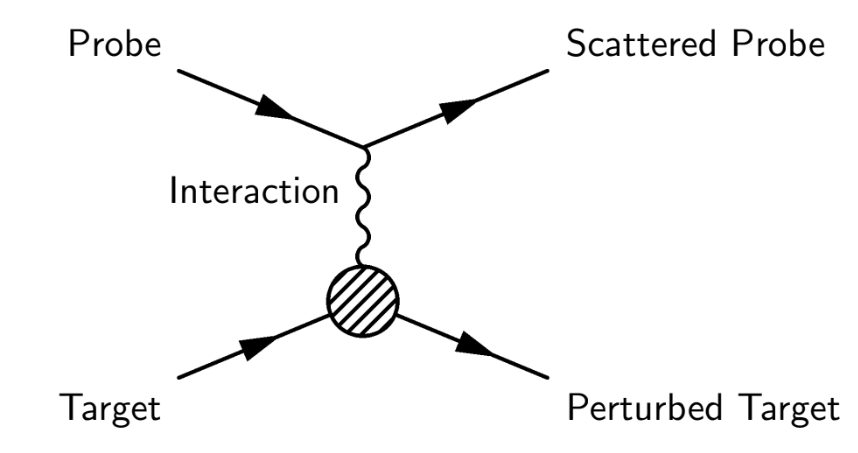

These effective models require tuning with external data as well as verifications or falsifications of their predictions. Theorists work with experimental physicists to determine what kinds of interactions can be probed with different kinds of experimental apparatus, including medium energy, highly polarized electron beams with fixed targets available with the CEBAF accelerator and the experimental halls at JLab. Scattering experiments specifically work by sending in probe particles that interact with the target material via physics interaction pathways, such as exchanging a photon, the force mediator of the electromagnetic force, and perturb the target and bounce off or produce reaction byproduct daughter particles to be measured by the experimental apparatus.

Experiment design and simulations

When a physics observable has been highlighted by theorists for measurement, experimentalists begin to determine what kinds of beam conditions, target systems, magnetic spectrometry, kinds of detectors, detector spatial, time, and energy resolutions, and radiation shielding needs they may have. These kinds of specifications can be done with back of the envelope calculations and working from previously successful similar experiments, but verifying the sufficiency of the proposed apparatus typically requires performing a simulation of the constituent pieces and the entire system.

These simulations can be done in various software packages, such as Geant4, COMSOL, TOSCA, or others for radiation propagation through targets, magnetic spectrometers, detectors, and radiation shielding.

Additional variations on popular packages like Geant4 have been developed specifically for medical physics applications, specifically TOPAS and GATE. The only significant difference between nuclear physics experiments and medical physics systems is the energy range in use, diversity of interactions within the target or patient, and the possible radiation environments. However, as ion therapies using particles even heavier than protons (Helium, Carbon, and Neon) are coming into use the distinction between accelerators, detectors, and radiation environments between the two worlds is becoming less significant.

Radiation Source (injector)

The electron beam used for a nuclear physics experiment at JLab begins its life when a laser impinges on a strained Galium Arsenide semiconductor crystal. The direction of circular polarization of the laser determines the spin direction of the electron. The electrons coming out of the crystal are accelerated with a high voltage gradient (like a capacitor) and are passed into additional accelerating, beam profile shaping, and polarization controlling systems downstream.

In the case of medical imaging and therapies the sources are quite similar. X-ray CT systems utilize a similar conversion mechanism, though in the reverse direction, where electrons incident on a heavy metal cathode will shine X-rays due to the high energy nature of the breaking interactions (Bremsstrahlung braking radiation). In positron emission tomography the source of radiation is radioactive decays of unstable nuclear isotopes. For proton or ion radiation therapy the source is very similar to the CEBAF electron beam, though without the same need for polarization control.

Radiation Acceleration (linear accelerator)

After the beam is produced in the injector it must be accelerated to the high energies needed for nuclear physics interactions to take place. The energies are related to the spatial size and time scales relevant to nuclear interactions via the de Broglie wavelength. As the energy increases the spatial distance that is probed by the incoming accelerated particle shrinks. The conversion factor is related to the Plank constant: h-bar*c = 197.3 MeV fm, and so a 1 GeV beam is sensitive to interactions that take place on the distance scale of 5 inverse femto-meters (also referred to as “fermi”), which is ~0.2 ^ 10-15 meters, or approximately one fifth of the size of a proton, whose mass is approximately 1 GeV. The time conversion comes from imagining how long it takes a particle traveling the speed of light (which is the fundamental speed limit on energy and information transfer) to traverse that distance; 1 femto-meter is traversed in 3.33×10^−9 femtoseconds, meaning the time scale is extremely short for interactions taking place at the sub-atomic nuclear scale. These conversion factors are a convenient way to visualize the distances, energies, and times involved in relativistic high energy physics.

The acceleration is done by filling cavities with radiofrequency (RF) radiation, similar to how a standing wave is set up inside of a microwave oven to deposit energy into your cold left-overs. The cavities at CEBAF are made of Niobium and are superconducting below 4 Kelvin (-269 degrees Celsius). Electrons that enter with the right timing, in phase with the frequency of the standing radio-waves, will absorb some of the RF energy and be accelerated. Chaining many of these together permits acceleration to relativistic energies along a single linear accelerator on the north or south side of CEBAF.

Radiation Delivery (optics)

The accelerated electrons need to be kept in tight bunches as they travel around the accelerator, bend around the east and west arcs for further acceleration, and are delivered to the halls for scattering on the targets. There are many dipole and quadrupole magnet systems along the accelerator to provide this beam shaping and transport to the halls. Additional scattered beam shaping and transport may be done in the detector systems downstream of the target.

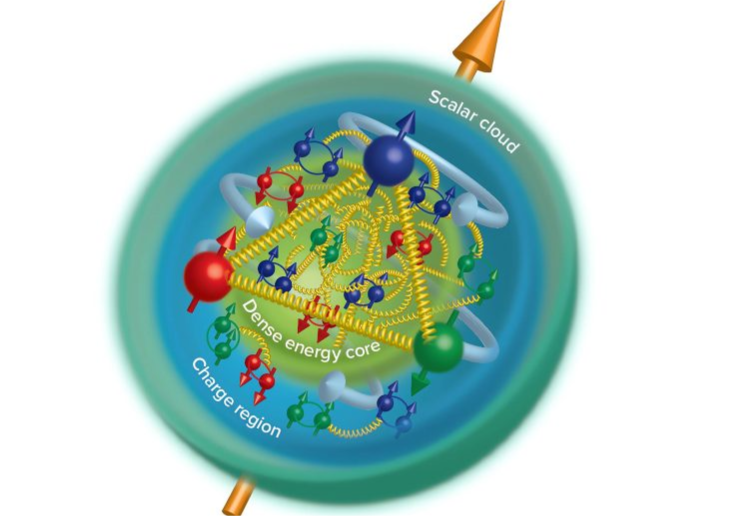

Nuclear Targets

The beam is scattered against isotopically pure targets, made of matter of interest to the experiments. Targets at JLab may range from hydrogen or deuterium gas or other light isotopes with interesting quantities of neutrons and protons to pure Calcium-48 or Lead-208 targets. The goal for most experiments is to interact the electrons with the entire nucleus of the target’s atoms in one simple interactions. Or the goal may be to probe inside of the nucleus’ constituent protons and neutrons or to excite higher energy excited states of the nucleus or its constituents. The key to understand is that the incoming beam interacts with the target nuclear matter in a way that reveals information about its spatial distributions and possible spectrum of excited energy states.

For medical imaging scenarios the typical topic of interest is the location of radioactive material that you fed into the patient or the density distribution of biological matter, to recognize anatomical features of interest or tumors.

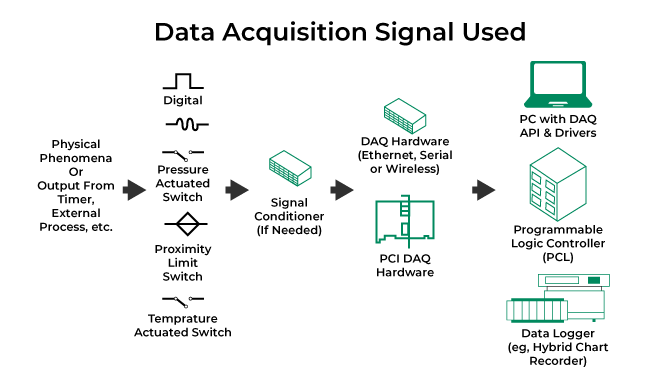

Radiation Detection, Data Acquisition, and Online Monitoring

Detectors are used to measure the kinds of product particles and their spatial and energy distributions. Detectors range from simple determinations that a particle passed by, by producing a pulse of optical photons that may be read out by a photon-sensitive detectors like a Photon Multiplier Tube (PMT) or can be as complicated as a system that registers the total amount of energy deposited in a chunk of lead-tungstate glass and measures the difference in time and position of the particle’s trajectory with gas-based tracking detectors and high time-resolved data readout systems.

For medical imaging systems the most common detector technologies are scintillating crystals that convert X-rays and gamma rays into optical photons that are read out by PMTs or Silicon Photo Multiplier (SiPMs) whose electrical pulses are processed with discrete circuit components or separate amplifiers and analog to digital converters. Recently on the rise are direct photo-electric effect conversion of the high energy photons within semiconductor materials like Silicon or Cadmium Zing Telluride (CZT) whose electrical pulses are read out by application specific integrated circuit (ASIC) dedicated signal processing computer chips. These ASIC approaches are also used by some contemporary SiPM based scintillator detectors, such as the one used by the Streaming Read-Out PET detector system being developed in the JLab Radiation Detector and Imaging Group and tested at the University of Maryland at Baltimore.

Online analysis is performed while the data is being collected. This can be as simple as watching the number of events that pass the triggering threshold increase over time, or it can be as complicated as a real-time updating image of the fully processed and reconstructed data, generated while the data is still being collected.

Data Analysis and Scientific Computing

The data needs to be analyzed after it is collected. This includes performing calibrations where default values (referred to as “pedestals” or backgrounds) are measured without any external beam or radiation sources, in order to characterize the baseline offsets and noise of the systems. Gain calibrations or relative energy thresholds may also need to be calibrated with standard references. For complicated beam delivery systems like at CEBAF, the beam current and position must be monitored to ensure no extreme conditions are present and to remove data when the beam is off due to accelerator protection system alarm trips. Beam position and energy information present in the beam delivery position monitors may also be used to correct individual events’ kinematic parameter estimations away from the overall average or to characterize unwanted additional background correlations.

Scientific computing is the general term for data analysis software and large-scale computer clusters used to convert raw binary data information obtained from the detector systems into meaningful descriptions of signal with precisely calibrated quantitative information. Jefferson Lab offers the interactive farm (ifarm) for interactive sessions and batch job submission. In this way a large data set may be broken up into many smaller ones that can be processed conveniently in parallel, or an experiment that takes data over many days can send data corresponding to individual configurations for separate analysis. The ifarm is also useful for running large quantities of simulation data, needed to precisely sample the large space of parameters in a simulated experiment’s geometrical conditions and in the potential physics interaction conditions.

When theoretical or experimental data has been processed sufficiently, it is analyzed and compared with expectations. The results of the analysis are then described in both qualitative and technical detail, to a level that expert researchers not affiliated with the work should be able to reproduce and verify the results independently and are published in a peer reviewed academic journal.

Scattering Experiments in a Nutshell

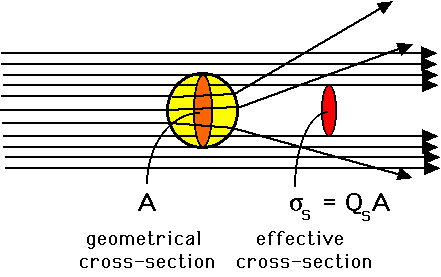

Quantum scattering can be understood at a variety of levels. The simplest way to approach scattering experiments is to imagine that you are not able to directly see an object with visible light and your own eyes, but you want to use some sort of probe that is able to interact with the object to determine its physical presence, quantity, and size. An example is to imagine throwing darts in a flat random distribution past a mystery object and then checking the shadow of the dart pattern on the wall behind it. As you increase the number of darts you will get a more precise and crisper image of the shadow of the object on the wall. Additionally, if you know the area of the pattern you threw the darts and how many you threw and count how many are missing then you can calculate the area of the object that absorbed them as the relative difference, even if it is a strange shape that is difficult to make out – this is called a cross-section measurement, because it is sensitive to the spatial area of the 2-D cross-sectional slice against which you projected your projectiles. This is the basic idea behind measuring cross-sections for quantum scattering processes, explained in more detail later, and is also the key idea behind Monte Carlo random sampling for simulations of expected outcomes for either large complicated or intrinsically probabilistic (quantum mechanical) systems.

If instead you have a large quantity of small objects and you want to know how many there are, you can similarly throw a large number of darts past them on to the wall, and now instead of looking for the shape you can simply check the relative quantity of missing darts – this tells you the total cross section for absorption, which may give you enough information to proceed – and will let you calculate the quantity of small objects present if you know the size of the individual items. Scattering through a material whose probability of absorption (scattering cross-section) is not infinitely high or depends on parameters such as the size of the projectile or its speed will complicate things, but as long as you keep track of the kinematic parameters the approach is generally the same. If there is a fixed probability of interacting as a projectile passes through matter, then the quantity of surviving projectiles as a function of distance travelled will be exponentially decaying. In quantum mechanics, where this is the common scenario, it is referred to as the “penetration depth” or “radiation length” – the distance through which 1/e (Euler’s number) or 1/2 fraction of the incoming particles are absorbed.

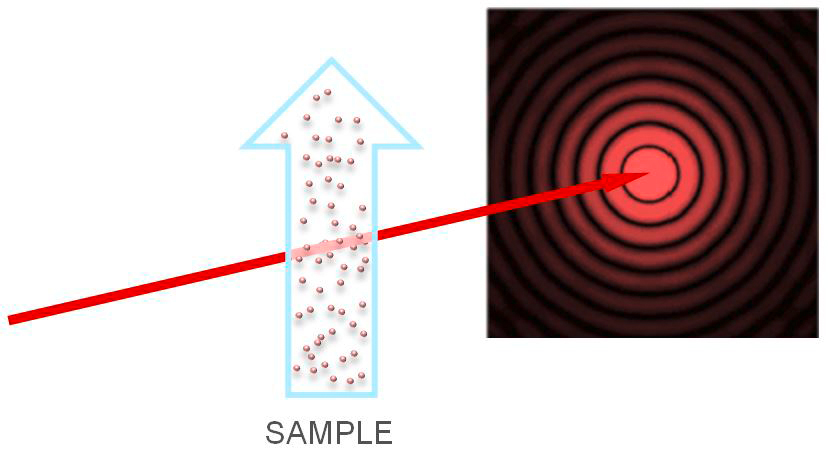

In quantum mechanics, which includes the scattering of photons of visible light past microscopic (10^-6 meter, micro-meter, “micron”) scale objects, similar in size to the wavelength of the light, the wave/particle duality nature physics becomes relevant. For quantum mechanical particles interacting with objects similar in size to their wavelength (the de Broglie wavelength, inversely proportional to the relativistic momentum for massive particles like electrons from an accelerator), the wave nature of their probability distributions comes in to play and the scattering patterns downstream of the interaction point can be understood as multiple wavefronts re-scattering off of the edges of the material and combining to generate the probability distributions on the detector surface downstream.

The two figures above describe the double slit experiment for laser light and a point-spread function diffraction pattern for coherent radiation scattering past a small spherical target sample collection.

In nuclear physics and some chemistry scenarios the scattering can deposit energy from the incident scatterer onto the target systems, which will appear as energy dependent changes in the probability of a scattering to occur. The transfer of momentum to the target is like a billiard collision, where the momentum is conserved within the total system. The transfer of energy into excited states transfers momentum into an excited system, like in the case of a hydrogen atom’s electron being excited to a higher orbital energy level or the production of decay or daughter product particles, such as a water molecule being shattered into an H+ and OH- pair of radicals. These two kinds of scattering processes (momentum conserved – elastic scattering vs. excited state – inelastic scattering) may both happen with different probabilities in a single scattering experiment scenario, and do not have the same resulting outgoing wave-propagation diffraction patterns.

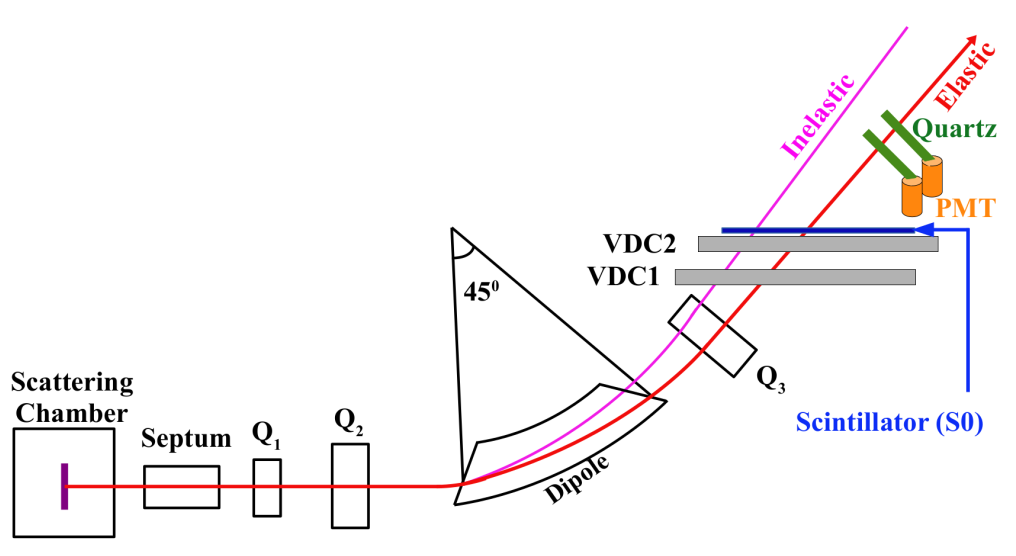

Different scattering processes taking place in the same scattering experiment can be distinguished by measuring the energies of the outgoing particles that produce two different probability distributions of scattering taking place at different angles and different energies. Nuclear physics experiments at Jefferson Lab can be thought of as very large-scale systems (typically because of the need for large magnets to spread out particles according to their outgoing momentum) designed to measure relatively rare interactions and to place detectors at specific locations relative to the center, to measure the high and low probability rings in the quantum-mechanical scattering diffraction patterns. These nuclear experiments measure relative scattering probability rates as a function of energy and angle and use that information to infer the size, quantities, and possible interactions and excited states of the nuclear targets. High energy particle physics experiments are similar, though they typically are more interested in studying the interaction forces and intermediate decay product particles involved in the scattering interactions directly, rather than the targets that are interacted with.

Medical imaging systems rarely need to consider the wave/particle duality and quantum interference picture of scattering, as the energies are much lower, and the size of the objects being studied are much larger than those where the wave nature become relevant. One modern imaging system where wave dynamics are important however is the use of microwave radiation for imaging with Terahertz non-destructive evaluation imaging (such as the airport personnel scanners that you stand in for security screenings). Another is X-ray dark field or diffraction imaging using the interference patterns to infer crystal structures or measure high resolution spatial distributions, which are generally impractical for medical imaging purposes. Medical imaging with radioisotope tagged tracer molecules frequently take advantage of weak nuclear decays to allow for finding hot spots where biological functional processes are taking place, typically overly energy hungry tumors absorbing excess Fluorine-18 tagged deoxy-glucose.

Conclusion

Please follow up with the cited resources above or below to go into more detail on any of the concepts described above and try to understand how nuclear physics and medical imaging and therapy systems work similarly or differently, and how the theoretical, simulation, delivery, detection, and analysis tools are conceptually shared between the two.

Further Recommended Reading:

- Skim over: the Intro and “Types” sections of the Wikipedia article on medical imaging: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_imaging#Types

- Skim over: the Wikipedia articles on

- Scintillation counters: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scintillation_counter

- Gaseous Ionization detectors: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaseous_ionization_detector

- Semiconductor detectors: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semiconductor_detector

- Calorimeters: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calorimeter_(particle_physics)

- Read: Monte Carlo explanation – https://eight2late.wordpress.com/2011/02/25/the-drunkard%E2%80%99s-dartboard-an-intuitive-explanation-of-monte-carlo-methods/

- Read: The Power of Proton Therapy – Symmetry Magazine: https://www.symmetrymagazine.org/article/december-2008/power-proton-therapy?language_content_entity=und

- Read: Introduction to Monte Carlo Simulation, AIP Conf Proc. 2010 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2924739/

- Skim over: Detectors for Particle Physics, D. Bortoletto https://indico.cern.ch/event/387976/attachments/1124401/1605557/daniela_l2.pdf

- Paywalled and very advanced description of scattering and diffraction for nano-particle characterization, for future reference: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43586-021-00064-9