Everyone has heard stories of incredible research results powered by immense budgets or extremely risky gambles. The story comes to mind of the three graduate students assigned by Enrico Fermi to “suicide squad” duty – to pour cadmium on top of the University of Chicago’s first ever sustained nuclear fission reaction in the case of a run-away reaction chain, or other stories of sometimes catastrophic handling of fissile materials. Another case is the experiment that garnered Leon Lederman the Nobel Prize, where he aggressively hijacked his graduate student’s entire experimental set up to test an idea about parity violation he borrowed heavily from C.S. Wu. What you don’t hear about very often are cases where incredible research results are achieved without cutting corners on safety for the researchers or the engineering systems involved, but that also manage not to break the bank.

Academic tenure-track careers are built on reputation, domain-specific knowledge, and demonstrated achievements, especially those built in the face of hardship and insurmountable odds. In contrast, practicing safety requires going slow, admitting one’s gaps in knowledge, and slowing down and even stopping work if things are not clear or conditions no longer permit optimal work practices.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of scientists who start down the tenure-track academic career path will not complete their journey, instead either transitioning to alternative academic, national laboratory, or industry research positions, or altogether leaving physics research and leaving the field to pursue data science, financial technology or other careers. Meanwhile, there is a perceived threat to one’s personal identity from, and consequent cultural stigma against, leaving the tenure-track academic career path or going to industry research, and even more-so with leaving the field entirely, and as such very little institutional or cultural support is provided to early career researchers to train them on how to succeed in or even how to search for jobs outside of the assumed tenure-track careers.

Without being equipped or encouraged to seek out non-tenure-track careers, and with the very small number of academic positions open for the large pool of qualified applicants, early career scientists can become very competitive and averse to showing any weakness in order to build their reputations to further their careers. This mentality causes anxiety and isolation, builds up pressure to always perform the best work and achieve impressive results, and leads to taking shortcuts in an “ends justify the means” way. One’s identity may even become subsumed by their research, especially in the publish-or-perish academic system. Under these circumstances, when safety considerations threaten to interfere with planned work, it is possible that a person intent on pursuing an academic career therefore may, for whatever reason, pay insufficient attention to safety or even intentionally take unnecessary risks to get ahead.

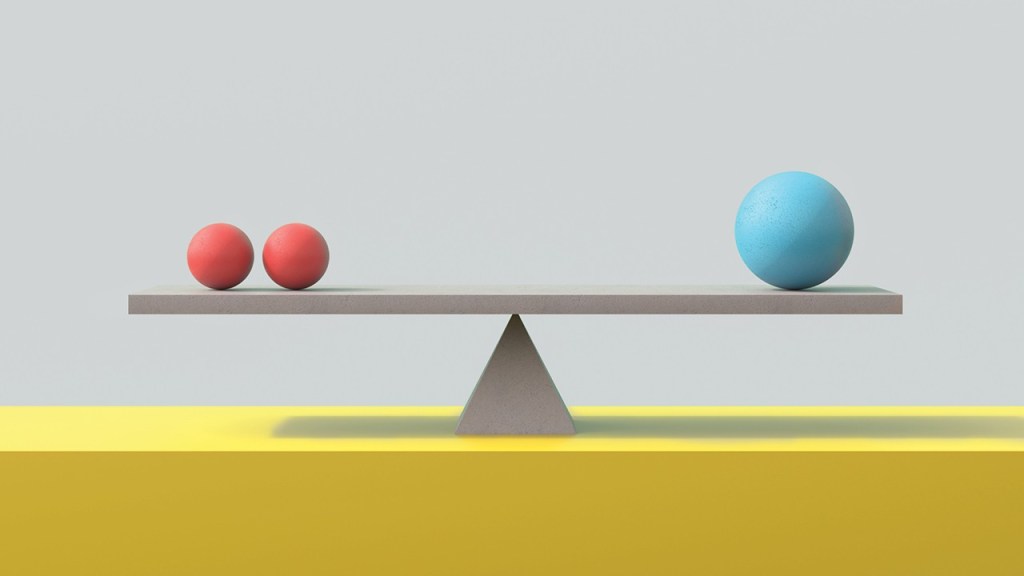

In an environment of academic research where permanent academic positions are scarce due to insufficient funding or overcrowding lower down the academic ladder, any increase in safety controls for the engineered systems will exert a pressure on the people struggling within that academic system. This pressure does not have to manifest as unsafe behavior, but it often does manifest as a general feeling of unease, insecurity, and generally a lack of feeling “safe” in one’s career. In this model I am proposing, I see funding for academics and engineered systems as a sort of fixed quantity, insufficient to wash away all technical issues or smooth over all career concerns, and therefore allowing this balancing act between a psychological sense of security and a real sense of engineering safety. When already anxious researchers enter an environment where the stability of the engineered systems is perpetually in question due to either insufficient funding to operate at full capacity as promised or a tangible precariousness coming from safety barriers and overhead, they will feel a pressure to work as hard as possible whenever the engineering systems are available – whenever the funding is flowing and nothing has been shutdown or paused for inspection.

My proposed solutions to these problems by no means lie within reducing standards or actual degrees of safety for engineered systems or researcher personnel, but in uncovering and transforming the actualities and perceptions of insufficient funding for academic careers. The truth is that most people who set down an academic path will not follow it to completion – my question is: can we change that by redirecting or changing the general culture’s expected end-path goal or more straightforwardly by simply improving the success rates for those who are still intent upon achieving it.

A very straightforward, though difficult to actualize solution to the problem is to just increase funding: to lobby the U.S. Congress to distribute vastly more funds for researchers. The most effective mode of increasing funding would be to bolster academic independence for early and mid career researchers. The trend in recent decades has been to turn professors into ever-older and ever-more administrative directors ruling fiefdoms full of graduate students and post-docs. This trend needs to be reversed in favor of academic independence for post docs and professors at earlier stages in their careers and an increase in the expectation that professors engage in hands on research activities. The trend of the average age of substantial grants being awarded increasing over time needs to be reversed as well. Mid-career research positions other than assistant and associate professor positions need to be developed, normalized, and encouraged. A similar, though less desirable solution may be to reduce the number of positions opened for researchers earlier in the career path – limiting the number of PhD positions made available and requiring research groups to treat post-docs less haphazardly, as more permanent and important members.

A second simple, but difficult to discuss and systematize solution is to point out to everyone that the funding situation for early career researchers is not actually so dire: to encourage early career researchers to embrace and seek out research positions in industry where the funding is plentiful. There are problems with this, not the least of which is a complete lack of cultural acceptance within academia and a consequent information vacuum for how to successfully pursue a career in industry. Additionally, the space of research positions that fall outside of morally black or gray areas, or that do not require citizenship or security clearances, is also a significant barrier.

However, the vast majority of people who embark on academic journeys do end up in industry research positions, and so the most obvious solution to the anxiety, insecurity, and under-funding problem in academia is to wholeheartedly embrace academia-to-industry career transitions. A key distinction that must be consciously made when pivoting toward seeking industry research careers during early academic training is to cultivate a technical skill development and marketing mentality toward one’s time as an early career researching. This is opposed to the traditional, pre-large scale collaborative era, career development approach of focusing on building a large body of domain specific knowledge and demonstrating one’s place in the academic hierarchy.

My proposal for facilitating this cultural sea-change is to advertise my own brief experience in industry, emphasize the importance of transferrable skills and collaboration over the accumulation of domain knowledge, and seek to build as many collaborations between academic, government, and industrial research as possible, and to draw those who have transitioned to industry research back into the science communication ecosystem that the academic and government researchers inhabit.

Taking these points into consideration, my plan is fourfold – first, to yell into the void engage politically to lobby congress to increase funding for science and to diversify the federally funded types of career paths and early career academic position titles; second, to share my experience transitioning between academia, industry, and government research positions as an early career scientist; third, to build collaboration and science communication bridges between academic, industry, and government researchers and audiences; and lastly, to develop resources and share the career development skills and awareness necessary to pursue, apply for, and secure research jobs in industry for those currently pursuing academia.